*The content of this page is a summary of Dr. Okano’s original paper. It was prepared by Dr. Okano for the patient page, to allow the general public to understand the findings of his research. Dr. Okano is an extraordinary doctor who always has the best interest of patients at heart. Our Foundation is very fortunate to have the opportunity to work with him, and we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to him for his hard work in summarizing the results of his study and his devotion to the research and treatment of citrin deficiency.

Analysis of daily energy, protein, fat, and carbohydrate intake in citrin-deficient patients: Towards prevention of adult-onset type II citrullinemia

Yoshiyuki Okano a,b, Miki Okamotob, Masahide Yazakic, Ayano Inuid, Toshihiro Ohurae, Kei Murayamaf, Yoriko Watanabeg, Daisuke Tokuharah, Yasuhiro Takeshimaa

We conducted a survey on food preference and collected a food diary in 2018 from patients and control subjects. We would like to share a part of the findings from the study on energy and nutrients. The full text is also available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2021.03.004

1.Methods

1-1. Study subjects

62 patients (36 males and 26 females, aged 2-63) and 45 control subjects (22 males and 23 females, aged 2-61) enrolled in this study. Family members living in the same household served as the control subjects.

39 out of 43 patients in the 2-16 age group were diagnosed with NICCD during infancy and were able to receive an earlier dietary intervention. The remaining 4 patients were diagnosed with citrin deficiency during the adaptation/compensation period. Out of 10 patients in the 17-39 age group, 3 were diagnosed with NICCD during infancy, 5 during the adaptation/compensation period, and 2 were diagnosed with CTLN2 in adulthood. Among the 9 patients aged ≥40 years, 8 were diagnosed with CTLN2 and 1 was in the adaptation/compensation period. None of the CTLN2 patients had undergone liver transplantation at the time of the study.

1-2.Nutritional Evaluation

Patients and control subjects were asked to write a food diary for 6 days (minimum period: 3 days, average period: 4.6 days) and a nutritional evaluation of the diary was conducted. Their energy, protein, fat, and carbohydrate intake were calculated using the Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan 2015, and the subjects’ intake of energy, protein, fat, and carbohydrate was converted into percentages using the National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan 2016 as reference values (100%) for the matching sex and age.

Ex. The calculation of a 10yr old boy Sam’s diet shows the average energy intake being 2274kcal/day. According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan 2016, the average energy for a 10yr old boy is 1976kcal. Based on this data, Sam’s energy intake is 2274÷1976≒115%, in other words, 15% more than the general public.

2.Results

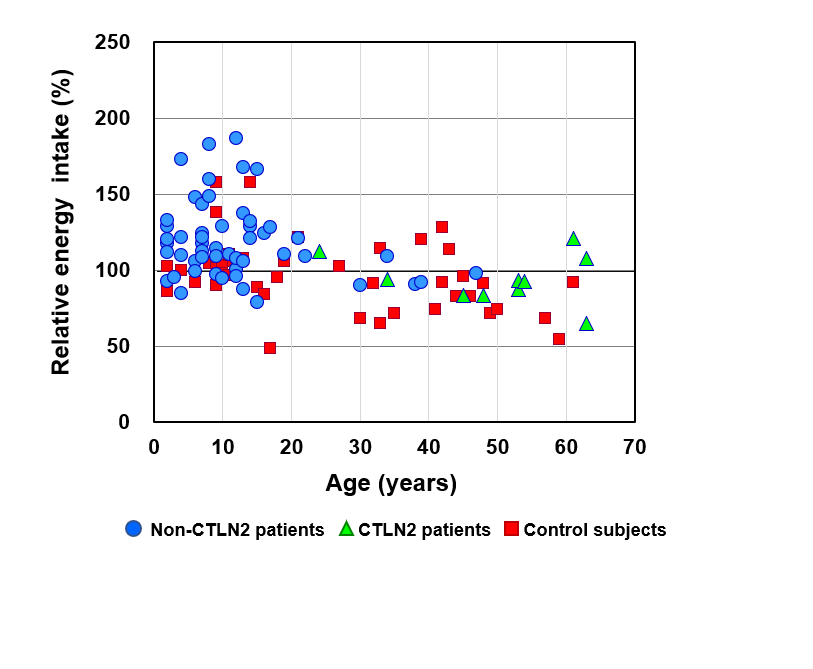

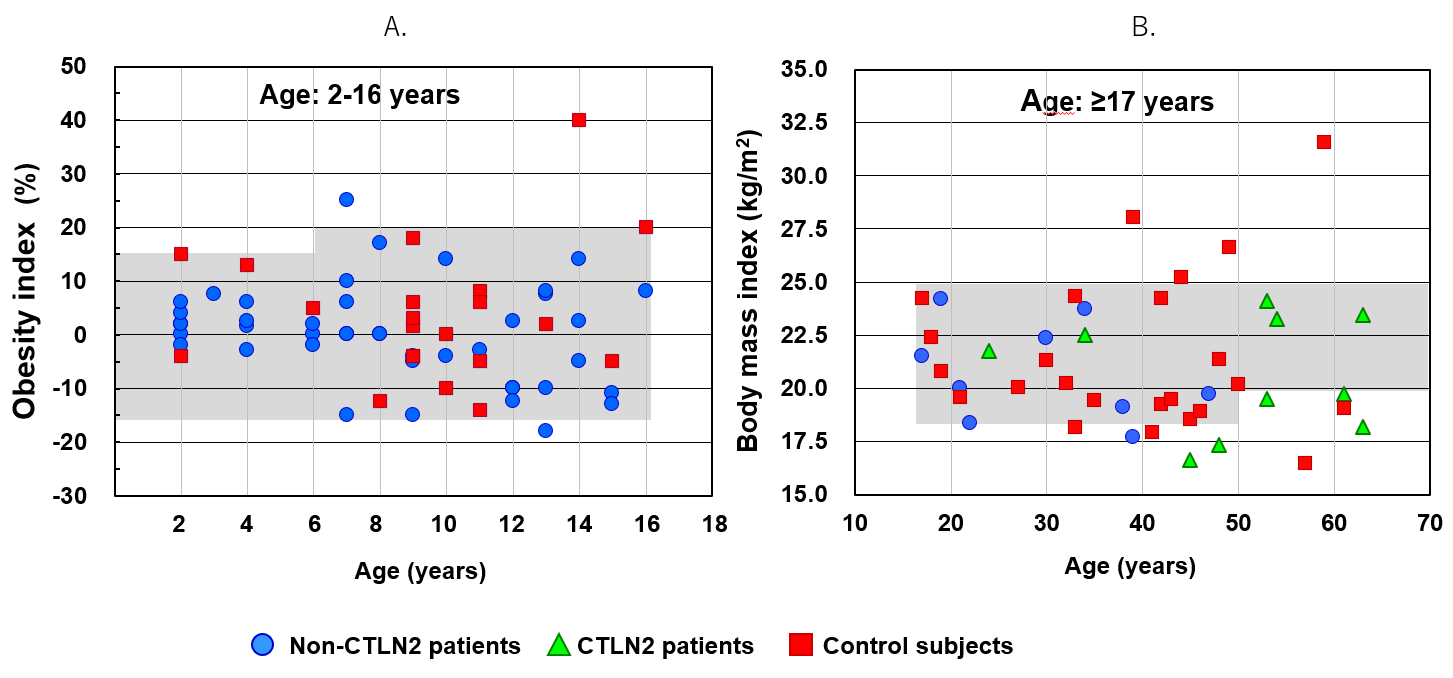

The scatter plots show the results of the present study. The horizontal line shows age, and the vertical line shows the result.

●:52 patients with citrin deficiency who have not had the onset of CTLN2

▲:10 CTLN2 patients

■:45 controls subjects

2-1. Energy

Figure 1 shows the relative energy intake of the patients and control subjects. ‘Relative energy intake’ means the percentage ratio of the subjects’ energy intake per day compared to the general Japanese population that is of the same age and sex.

As seen in Figure 1, both of the patient groups(● and ▲)took 15% more energy than the control group(■), which shows us that citrin deficiency patients take and need more energy than the general public.

Figure 1.

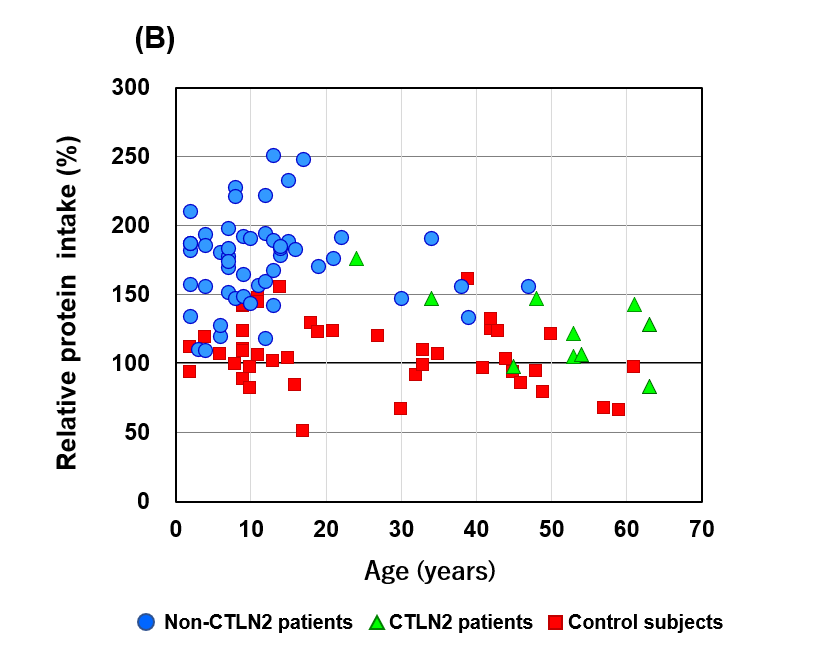

2-2. Protein/fat

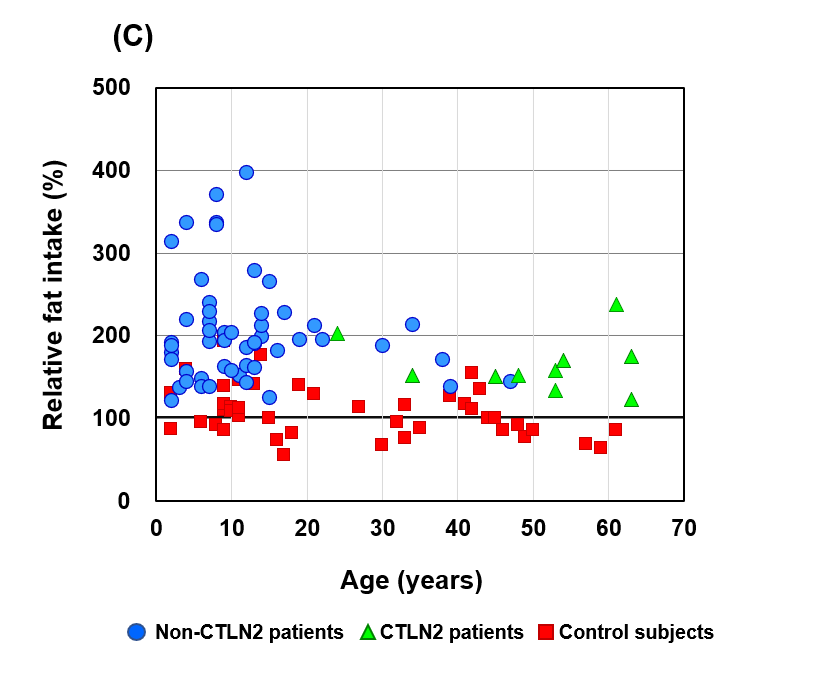

Figure 2 shows the relative protein intake and Figure 3 shows the relative fat intake of patients and control subjects.

As seen in the graph, both of the patient groups (● and ▲)consumed more protein and fat than the control group(■).

For protein, the average daily consumption for patients are as follows:

- Aged 2 – 16: 174%

- Aged 17 – 39: 172%

- Aged 40 and above: 121%

All of which were significantly higher than the general Japanese population (based at 100%).

Figure 2.

For fat, the average daily consumption for patients are as follows:

- Aged 2 – 16: 209%

- Aged 17 – 39: 188%

- Aged 40 and above: 161%

All of which were also significantly higher than the general Japanese population.

On the other hand, the protein and fat intake of the control group was around the same as the general Japanese population. The results here show that citrin deficiency patients take more protein and fat to compensate for the missing energy from carbohydrates that they avoid.

Figure 3.

2-3. Carbohydrate

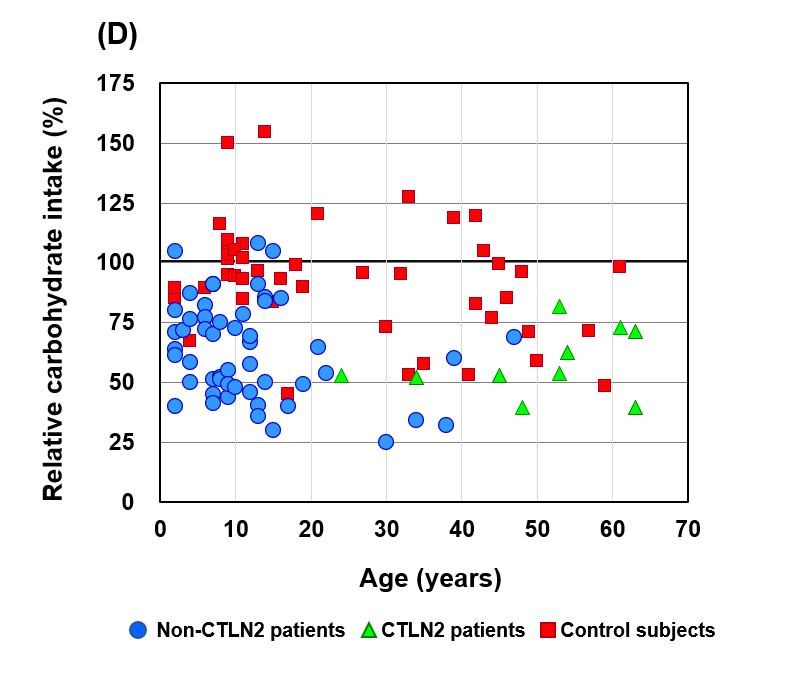

Figure 4 shows the relative carbohydrate intake of patients and control subjects.

Both of the patient groups (● and ▲)consumed less carbohydrate than the control group(■).

The average daily consumption of carbohydrates for patients are as follows:

- Aged 2 – 16: 67%,

- Aged 17 – 39: 46%,

- Aged 40 and above: 60%.

All of which are also significantly lower than the general Japanese population. The daily consumption of the control group is relatively similar to the general population.

Figure 4.

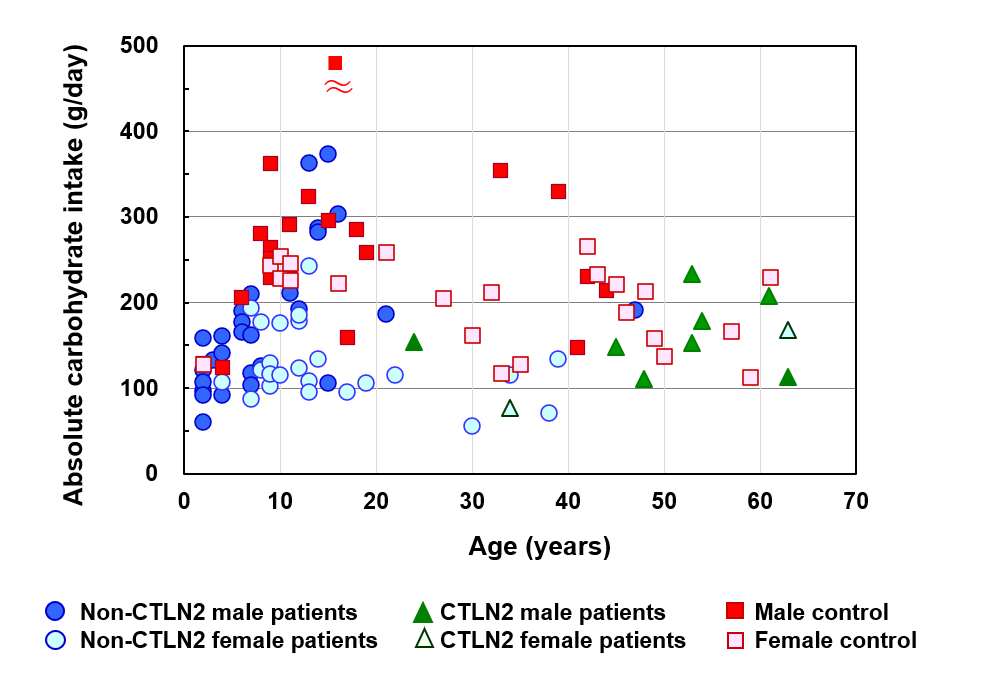

Figure 5 shows the amount of carbohydrate intake* per day in grams instead of the ratio (%).

The carbohydrate intake of both male(■) and female(□)control subjects simultaneously increased with the energy intake (Figure 1), and as seen in Figure 5, the carbohydrate intake of male control subjects peaks during adolescence, around 12-16 years old, at 380±122g /day.

On the other hand, the carbohydrate amount across all patients groups (●, ○, ▲, △)remained between 100~200g.

Patients with citrin deficiency maintained a carbohydrate intake of 100-200g daily, except for adolescent patients as they require higher energy consumption. The minimum amount of carbohydrate consumed is reported to be approximately 100g/day, therefore it can be concluded that patients take the minimum required amount of carbohydrate while avoiding excess intake.

* The amount of carbohydrate (g) refers to the amount shown on the nutrition information table often found on the package, and it is different from the food itself (ex. rice 100g).

Figure 5.

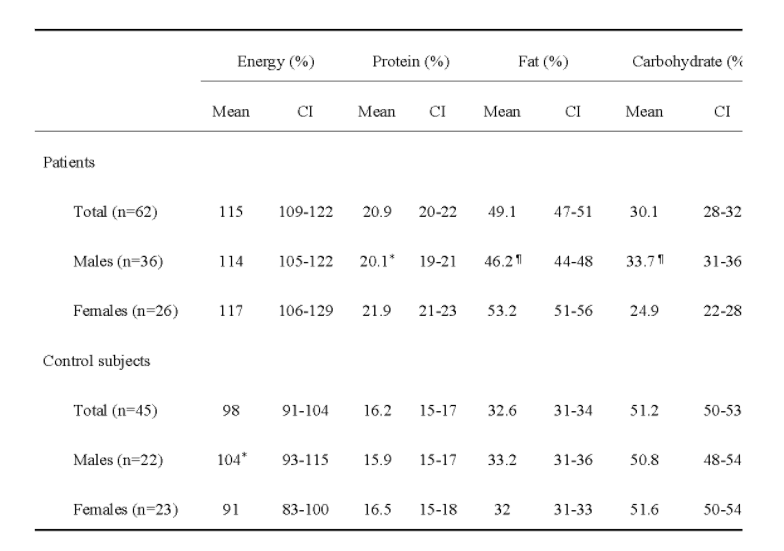

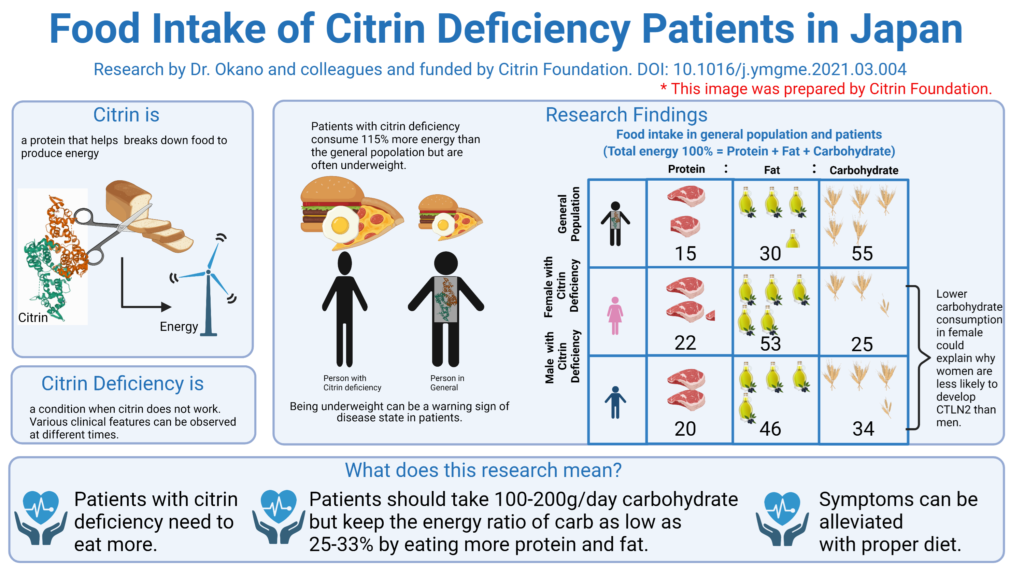

2-4. Energy and protein:fat:carbohydrate ratio(PFC ratio)*

Table 2 shows the average energy and protein:fat:carbohydrate ratio (P:F:C ratio) of the subjects’ diet according to the food diary. The average energy intake of patients was 115% compared to the general Japanese population regardless of gender. In the control group, males are observed to consume more energy than females but the age difference (average age of males is 19.6 years old; average of females is 31.4 years old) might have skewed the result.

The present study revealed that the P:F:C ratio of patients is 20:50:30, which shows an even higher protein and fat intake, and a lower carbohydrate consumption than the study 10 years ago. Patients are advised to have their diet evaluated from time to time and to maintain an average P:F:C ratio of around 20:50:30. Table 2 shows 1.8% more protein, 7.0% more fat, and 8.8% less carbohydrate intake in female patients compared to the male patients, while the control group showed no significant difference between the genders. Considering that there is only half the number of CTLN2 cases in females compared to males, and female patients consume a smaller portion of carbohydrates (24.9% carbohydrate in the P:F:C ratio) than male patients, it could suggest that a smaller portion of carbohydrate intake may contribute to fewer cases of CTLN2.

*P:F:C ratio: Energy is generated from protein, fat, and carbohydrates. The P:F:C ratio shows how much each nutrient constitutes the energy from the food source in %. For example, if 1 cup of milk is 140kcal and the P:F:C ratio is 20:50:30, the energy from protein is 28kcal, the energy from fat is 70kcal, and the energy from carbohydrate 42kcal.

Table 2.

p<0.05 and ¶p<0.001, between males and females (by Student’s t-test.).

CI: confidence interval.

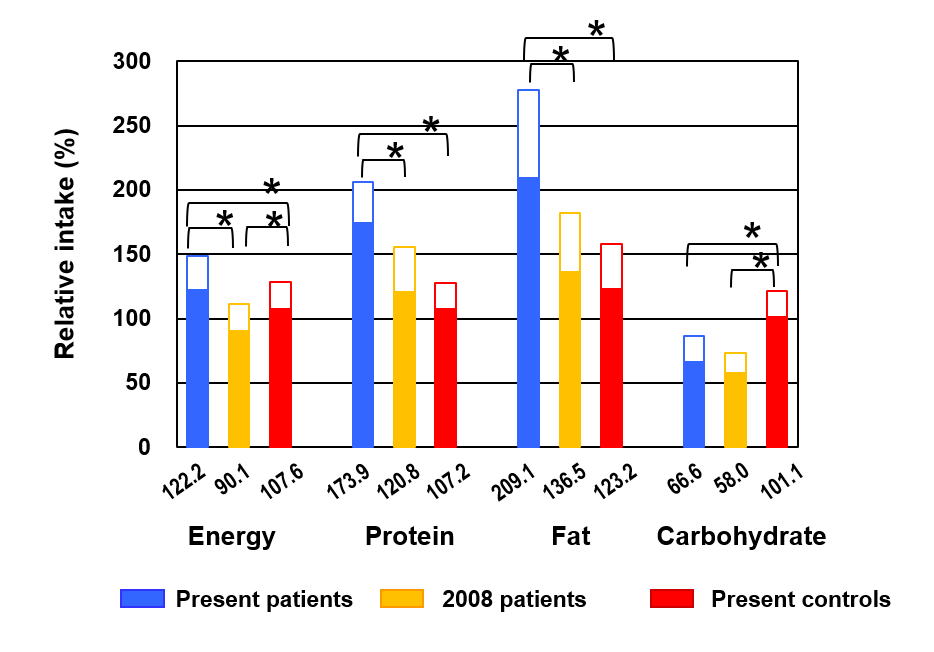

2-5. Changes in patients’ energy and nutrient intake over 10 years

The patients’ unique diet has been acknowledged from the beginning but no one could explain why. Additionally, diet consultation and intervention were not really called for until the year 2008 when Professor Saheki reported the low energy intake and unique P:F:C ratio in patients and pointed out the importance of dietary intervention. It has been 10 years since this report, and the result of the present study seems to reflect the changes in patients’ diet that the dietary intervention brought about. Comparing the dietary evaluation from 2018 with the one in 2008, energy, protein, and fat intake has increased while there was almost no change in carbohydrate intake (Fig.6). It seems patients are now able to consume enough energy from food, thanks to the active dietary intervention.

Figure 6.

2-6. Anthropometry of patients and controls

Anthropometry was measured using the obesity index for the 2-16 age group (Fig.7A) and BMI was used for patients that were 17 and older (Fig.7B). The figures show almost no difference in anthropometry between patients and controls (the grey area indicates the normal range).

In 9 patients above 40 years old, 8 had an onset of CTLN2, and of the eight, 5 were lean. These figures show that there are a few overweight patients and even several underweight patients in the older group even when they consumed more energy than the general Japanese population.

The study indicates that patients with citrin deficiency need more energy to sustain growth and a good physical build.

Figure 7.

3.Summary

This study analyzed the energy, protein, fat, and carbohydrate intake of 62 patients and 45 control subjects.

- Patients with citrin deficiency consume 115% of energy compared to the general Japanese population. This could be one of the means to prevent the onset of CTLN2.

- The confidence intervals of the targeted P:F:C ratio for patients are 20%–22%:46%–53%:25%–33%. Patients tend to limit their carbohydrate intake to the minimum required amount.

- The average P:F:C ratio for female patients is 22:53:25 while the average for male patients is 20:46:34, which highlights the low carbohydrate intake in female patients. This could explain the fewer number of CTLN2 patients in female patients than in male patients.

- The energy, protein, and fat intake of present patients were higher compared to the data from 10 years ago while carbohydrate intake remained the same. Almost all patients, except for those in adolescence, keep their carbohydrate consumption between 100~200 g /day.

- Being underweight could be a warning of the onset of CTLN2 for patients with citrin deficiency. Periodical check-ups for height and weight are very important.

Acknowledgment

This work was partially supported by a grant from Citrin Foundation.

a Department of Pediatrics, Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya 663-8501, Japan,

b Okano Children’s Clinic, Izumi 594-0071, Japan,

c Department of Biological Sciences for Intractable Neurological Disorders, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Shinshu University, Nagano 390-8621, Japan

d Department of Pediatric Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Saiseikai Yokohamashi Tobu Hospital, Yokohama 230-0012, Japan

e Division of Clinical Laboratory, Sendai City Hospital, Sendai 982-8502, Japan

f Department of Metabolism, Chiba Children’s Hospital, Chiba 266-0007, Japan

g Research Institute of Medical Mass Spectrometry and Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume 830-0011, Japan

h Department of Pediatrics, Osaka City University Hospital, Osaka 545-0051, Japan

Please find a graphical summary of this article here:

Created with BioRender.com